As the United States approaches its 250th birthday on July 4, 2026, Williamsburg, Virginia stands as one of the most consequential – and complicated – historic destinations in the nation. Long celebrated as a cradle of American democracy, this region also tells a deeper and more difficult truth: The country’s founding was shaped by Indigenous displacement, African enslavement, and the perseverance of people denied freedom, even as they built the infrastructure of the United States and sowed its wealth.

My first visit to Williamsburg and its surrounding areas came at a time in which revisionist historians are attempting to rewrite the messy racial past of this nation. I knew instinctively that traversing the region required standing firm in the knowledge that enslaved Africans were not peripheral to the nation’s founding, they were foundational. Their forced labor built the region, their resistance challenged its contradictions, and their perseverance continued to shape its future. Fortunately, Williamsburg and its neighboring cities have taken ownership of its history, good and bad, so concerns about being gaslit quickly faded.

To experience Williamsburg today, including Colonial Williamsburg, Jamestown Settlement, and nearby Yorktown, is to encounter the raw origins of America itself. At the center of this story are Virginia’s Indigenous people and Africans whose lives, labor, resistance, and resilience shaped a nation still reckoning with its provenance.

Before 1607: Virginia Indigenous Nations and a Living Landscape

The presence of the Indigenous and their displacement are foundational to understanding American history. For centuries before English colonists arrived, the Virginia landscape was home to thriving Indigenous societies. The Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom, composed of more than 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes, stewarded the land, waterways, and ecosystems of the Tidewater region. These communities possessed sophisticated political systems, agricultural practices, trade networks, and more long before Europeans set foot on Virginian soil. However, the arrival of English colonists permanently altered Indigenous life through land seizure, violence, disease, and forced cultural erasure.

Jamestown Settlement: Where the Colonists Waged Culture Wars

American history begins in Jamestown Settlement, where the earliest cultural collisions occurred. In 1607, colonists established the first permanent English colony on land already occupied by Indigenous people. Complex and often violent encounters between the colonists and the Indigenous people reshaped the region.

In 1619, another world-altering event occurred. Enslavers took West Central Africans from the Kingdom of Ndongo, which is present-day Angola, and brought them to British North America. These Africans, who included skilled artisans and tradesmen, were brought to Virginia to toil in fields of cash crops against their will. This marked the beginning of an African presence in what would become the United States of America.

Today, Jamestown Settlement recounts these early moments by recreating the environments in which Virginian Indigenous people, English colonists, and Africans interacted. Living-history programming and exhibitions also examine and interpret their interactions. These encounters planted the seeds of a new nation while laying the groundwork for slavery, racial hierarchy, and, eventually, resistance.

Williamsburg: A Capital Built by Enslaved Africans

By the time Williamsburg became Virginia’s capital in 1699, slavery had been codified into a rigid, race-based system. At this point in history, Africans comprised a substantial portion of the population. They were enslaved bricklayers, carpenters, coopers, blacksmiths, cooks, domestic workers, and field laborers whose expertise sustained the colonial economy.

In addition, enslaved Africans constructed Williamsburg’s most iconic structures, including the Governor’s Palace, the Capitol, churches, taverns, and private residences. Tobacco wealth flowed directly from enslaved labor. Slavery did not simply exist in Williamsburg – it was the economic backbone of the colony.

Education as Control: The Williamsburg Bray School

From 1760 to 1774, the Williamsburg Bray School was among the earliest institutions for Black education in North America. Led by Ann Wager, the school educated hundreds of enslaved and free Black children (ages three to 10) in Anglican doctrine, reading, and sewing for girls. Though its mission to persuade enslaved students that bondage was divinely ordained was deeply flawed, literacy carried unintended power. Hidden for more than 200 years on the College of William & Mary campus, the Bray School now stands in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area as the Foundation’s 89th original structure. It is a compelling reckoning of the contradictions of early Black education.

Resistance, Survival, and the Pursuit of Freedom

Despite relentless oppression, Africans in Williamsburg resisted in both overt and quiet ways. They preserved African traditions and built kinship networks, and also slowed labor, sabotaged systems of control, and escaped whenever possible. Colonial lawmakers responded with increasingly harsh slave codes, reflecting deep fear of Black resistance in a city dense with enslaved people.

Williamsburg’s location near forests, waterways, and northern routes made it a critical early corridor of escape. Long before the Underground Railroad was named, enslaved Africans relied on oral networks, free Black allies, and faith communities to pursue freedom.

Sacred Space and Black Spiritual Power

Black churches emerged as vital centers of resistance and survival. Free and enslaved Africans founded the First Baptist Church of Williamsburg in 1776, during the American Revolution. It offered sanctuary at a time when white congregations excluded Black Virginians and denied their full humanity.

First Baptist Church of Williamsburg remains one of the city’s most enduring Black institutions. The church’s historic bell, which has called worshippers to prayer for generations, rang during the 2016 opening ceremonies of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Its sound linked our enslaved ancestors in Williamsburg to a national reckoning with Black history nearly 250 years later.

Revolution Without Liberation

Williamsburg was a hotbed of revolutionary politics. Debates about liberty echoed through the halls of its institutions, yet freedom rarely extended to Black people. Enslaved Africans heard the rhetoric—and recognized its hypocrisy.

Some escaped to British lines after promises of emancipation. Others fought for the patriots, hoping service would earn freedom. While a few succeeded, most remained enslaved as the new republic preserved bondage while celebrating independence.

Yorktown and a Fuller Revolutionary Story

The American Revolution Museum at Yorktown expands the American Revolution narrative by centering the experiences of enslaved Africans, free Black people, and African-American soldiers. Through immersive exhibitions and living-history interpretation, the museum examines how Black Americans shaped the Revolution, and how its promises often excluded them.

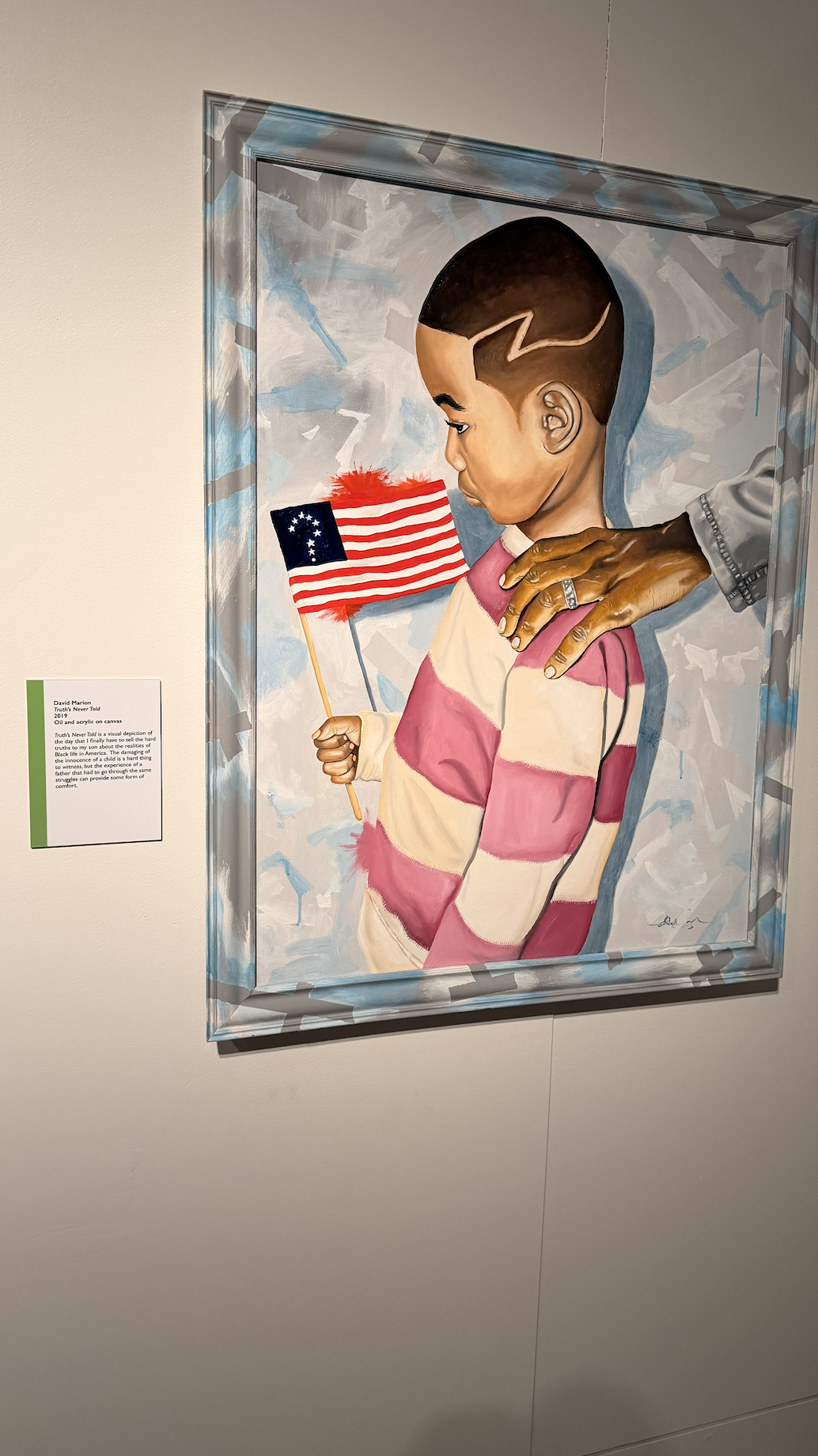

Williamsburg Today: A Destination of Truth and Reckoning

Williamsburg is increasingly committed to historical honesty now. Colonial Williamsburg has expanded its interpretation of enslaved life by naming individuals, restoring their quarters, and academic study rooted in Black voices. Similarly, Jamestown Settlement and Yorktown, together, contextualize the earliest cultural encounters that shaped the nation.

For travelers commemorating America’s 250th birthday, Williamsburg is not simply a historic destination, it is a site of reckoning, a place where Black history lives.

Our ancestors’ forced labor built this country. Their resistance challenged its contradictions. Their perseverance continues to shape America’s future through us.